Morning Alarm Skip Counting Game That Makes Math Fun for Kids (2025)

Morning Alarm Skip Counting Game That Makes Math Fun for Kids (2025) You know that moment when the alarm goes

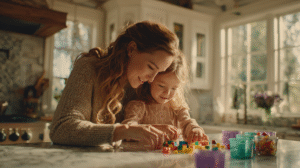

Snack math activities can turn an ordinary afternoon into a surprisingly rich learning experience.

“Mom, I’m hungry!” my 4-year-old announced yesterday afternoon, standing in front of the pantry with that familiar look of determination. Instead of grabbing the first box I saw, I paused and said, “Let’s count out 15 goldfish crackers together and see if we can make some patterns.”

What started as a simple hunger fix turned into 20 minutes of engaged mathematical thinking. We counted by fives, created color patterns, and even practiced subtraction when she ate some of her crackers mid-lesson. By the end, she’d satisfied her appetite and absorbed more number concepts than during our last formal math session.

As a former middle school math teacher turned mom of two, I’ve discovered that some of our most powerful learning moments happen in the kitchen—especially through snack math activities—with snacks as our manipulatives and hunger as our natural motivator. The beauty of these snack math activities is that they feel effortless to both parents and kids, all while building essential number sense skills.

Instead of mindlessly pouring snacks into a bowl, I’ve learned to turn portioning into purposeful counting practice.

“Can you count out 12 grapes for your plate?” I ask, and suddenly portion control becomes one of our go-to snack math activities—building one-to-one correspondence and number recognition without stress.

My 6-year-old practices counting accuracy while my 4-year-old works on number sequence and recognition. We also explore early multiplication concepts by creating groups: “Let’s make 3 groups of 4 pretzels each.”

This approach naturally teaches self-regulation around food while strengthening math skills. When children count their portions, they become more mindful about eating and develop better awareness of appropriate serving sizes.

The tactile nature of handling food while counting builds stronger neural pathways than abstract number work. Snack math activities like this turn everyday routines into powerful opportunities for discovery.

Snack foods offer incredible chances for pattern recognition and geometric thinking that feel natural and engaging.

We create sequences using colorful goldfish crackers: red, orange, red, orange—classic snack math activities that lay the groundwork for algebraic thinking.

Shape exploration becomes even more fun when we examine our snacks closely.

“This cracker is a square, but this cookie is a circle. Can you find all the triangular chips?”

From rectangles to triangles, math becomes part of the moment.

I also arrange apple slices and cheese cubes in alternating patterns, turning snack time into a playful geometry lesson. These hands-on snack math activities foster visual discrimination and early logic skills, all while feeding curious tummies.

And when children eat the patterns they create, they internalize the structure through experience, reinforcing the math in a deeply satisfying way.

Few snack math activities are more meaningful than learning fractions through real-life sharing.

When my kids split a granola bar, we explore halves, quarters, and fairness in the most tangible way possible.

“We have one granola bar for two people. What do we need to do to share it fairly?”

I ask, guiding them toward the concept of one-half—through their own problem-solving and hunger.

We explore quarters when slicing apples for four family members or measuring trail mix portions. Each piece becomes a fraction lesson, eaten and understood.

These snack math activities teach not only mathematical reasoning but also cooperation and fairness—life skills baked into every bite.

Snack math activities shine when math problems emerge naturally.

When my son eats 3 crackers from a set of 10, he learns subtraction not from a worksheet but from his own plate.

“You started with 8 strawberries and ate 3. How many do you have left?”

The physical act of eating provides instant feedback and makes the operation memorable.

We also practice addition: “You have 5 grapes and 4 crackers. How many snacks do you have in total?”

Snack combinations become real-world addition practice.

Because the stakes are real (“How many snacks do I get to eat?”), these snack math activities hold emotional value, leading to stronger engagement and retention.

Preparing snacks becomes another form of hands-on math. Measuring out cereal, portioning trail mix, or comparing bowls of crackers—all of these are rich snack math activities that teach volume, weight, and quantity.

“Let’s measure one-half cup of trail mix,” I say, letting them scoop and level ingredients themselves.

They gain confidence with measuring tools and understand precision through action.

Visual comparisons also build reasoning: “Which bowl has more?” or “Is this apple slice bigger or smaller than the other?”

These prompts turn snack prep into playful exploration.

The kitchen becomes a lab, and these snack math activities provide a low-pressure, delicious way to build confidence in measurement and comparison.

The most effective math learning often happens when kids don’t realize they’re doing math at all.

With snack math activities, we make numbers part of joyful daily rituals—building number sense through food, play, and curiosity.

By associating math with positive experiences like sharing, discovery, and satisfying hunger, we create confident learners who see numbers as useful and approachable.

This style of learning also respects how children develop: through concrete, sensory experiences.

Snack math activities provide the perfect medium—hands-on, edible, and naturally motivating.

Because sometimes, the most delicious lessons are the ones that sneak in between bites—when every cracker counts toward building bright, curious minds.

Morning Alarm Skip Counting Game That Makes Math Fun for Kids (2025) You know that moment when the alarm goes

Morning Weather Temperature Math: Simple Daily Learning Fun “Mom, is 45 degrees cold or hot?” My 8-year-old son Jake asked

Kitchen Timer Math Challenges: Fun Ways Kids Beat the Clock Have you ever watched your child race against time during

*Also read:

25 Brilliant LEGO Math Activities to Build Number Sense and STEM Skills at Home

Teach Kids to Tell Time: The Clock Game Every Parent Should Try at Home